A successful Citizens’ Assembly strengthens public trust, produces reliable outputs that garner legitimacy, and has an impact on public decisions. To run such a process, it is important to set the scene and put in place the conditions for success. This section of the guide lays out the conditions, and chapters that follow provide further details.

Following the OECD Good Practice Principles

The good practice principles for running Citizens’ Assemblies have been developed based on analysis of close to 300 examples of Assemblies in collaboration with an advisory group of leading practitioners from government, civil society, and academia. When in doubt, always refer to them as guidance on what constitutes a high quality Citizens’ Assembly.

Explore the principles:

1. Purpose

The objective should be outlined as a clear task and is linked to a defined public problem. It is phrased neutrally as a question in plain language.

2. Accountability

There should be influence on public decisions. The commissioning public authority should publicly commit to responding to or acting on Members’ recommendations in a timely manner. It should monitor the implementation of all accepted recommendations with regular public progress reports.

3. Transparency

The deliberative process should be announced publicly before it begins. The process design and all materials – including agendas, briefing documents, evidence submissions, audio and video recordings of those presenting evidence, the Members’ report, their recommendations (the wording of which Members should have a final say over), and the random selection methodology – should be available to the public in a timely manner. The funding source should be disclosed. The commissioning public authority’s response to the recommendations and the evaluation after the process should be publicised and have a public communication strategy.

4. Representativeness

The Assembly Members should be a microcosm of the general public. This is achieved through random sampling from which a representative selection is made, based on stratification by demographics (to ensure the group broadly matches the demographic profile of the community against census or other similar data), and sometimes by attitudinal criteria (depending on the context). Everyone should have an equal opportunity to be selected as Members. In some instances, it may be desirable to over-sample certain demographics during the random sampling stage of recruitment to help achieve representativeness.

5. Inclusiveness

Inclusion should be achieved by considering how to involve under-represented groups. Participation should also be encouraged and supported through remuneration, expenses, and/or providing or paying for childcare and eldercare.

6. Information

Assembly Members should have access to a wide range of accurate, relevant, and accessible evidence and expertise. They should have the opportunity to hear from and question speakers that present to them, including experts and advocates chosen by the citizens themselves.

7. Group deliberation

Assembly Members should be able to find common ground to underpin their collective recommendations to the public authority. This entails careful and active listening, weighing and considering multiple perspectives, every Member having an opportunity to speak, a mix of formats that alternate between small group and plenary discussions and activities, and skilled facilitation.

8. Time

Deliberation requires adequate time for Assembly Members to learn, weigh the evidence, and develop informed recommendations, due to the complexity of most policy problems. To achieve informed citizen recommendations, Members should meet for at least four full days in person, unless a shorter time frame can be justified. It is recommended to allow time for individual learning and reflection in between meetings.

9. Integrity

The process should be run by an arm’s length co-ordinating team different from the commissioning public authority. The final call regarding process decisions should be with the arm’s length co-ordinators rather than the commissioning authorities. Depending on the context, there should be oversight by an advisory or monitoring board with representatives of different viewpoints.

10. Privacy

There should be respect for Members’ privacy to protect them from undesired media attention and harassment, as well as to preserve Members’ independence, ensuring they are not bribed or lobbied by interest groups or activists. Small group discussions should be private. The identity of Assembly Members may be publicised when the process has ended, at the Members’ consent. All personal data of Members should be treated in compliance with international good practices, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

11. Evaluation

There should be an anonymous evaluation by the Assembly Members to assess the process based on objective criteria (e.g. on quantity and diversity of information provided, amount of time devoted to learning, independence of facilitation). An internal evaluation by the co-ordination team should be conducted against the good practice principles in this report to assess what has been achieved and how to improve future practice. An independent evaluation is recommended for some deliberative processes, particularly those that last a significant time. The deliberative process should also be evaluated on final outcomes and impact of implemented recommendations.

Connection to public decision making

Making sure a Citizens’ Assembly will have an influence on public decisions is the most important task. The commissioning public authority, institution, or organisation should publicly commit to responding to or acting on recommendations developed by the Assembly in a timely manner. This includes having early-stage conversations with a range of stakeholders who will be involved in various ways. A successful process often involves securing cross-party or cross-institutional support for the Assembly and keeping relevant civil society organisations and other institutions informed from the start.

Time and resources

Running a Citizens’ Assembly requires sufficient time and a dedicated budget.

Typically, at least two months are needed to secure a clear commitment from public authorities and to design the Assembly. It can take a further two months to run the lottery process for selecting Assembly Members.

Finally, the deliberation will take at least four full days, often spread over several months. Deliberation requires adequate time for learning, weighing up the evidence, and developing informed recommendations, due to the complexity of most policy problems.

The size of budget required will depend on the context, size, and length of the Assembly, ranging from 47.500 USD for a small local level Assembly in Brazil to several million euros for a large national level Assembly in France. A significant part of the budget goes into compensating Assembly Members for their time and hiring skilled facilitators.

Citizens' Assembly budget examples

From a resourcing point of view you will also need to assign a main coordinator or a team (to manage the process), and to tap into diverse competences in the organisation - ranging from communications to project management and expert knowledge of a specific policy area, as well as deploying technical resources such as an online platform or website.

Breaking down barriers to participation

The main motivation to participate is the commitment by a public institution to take into account the Assembly’s recommendations and use them as a basis for laws and policies which impact the real world. To ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to accept the invitation, it’s important to minimise barriers to participation by:

- Providing financial remuneration or honorariums

- Covering expenses

- Providing or paying for childcare and eldercare

- Choosing an accessible location

- Giving enough information about what being an Assembly Member entails and the time commitment required

- Understanding and addressing local barriers to participation in a specific context

How much should Assembly Members be paid?

The amount depends on the context. Here are a few examples from recent Citizens' Assemblies.

Considerations for and benefits of institutionalisation

To maximise the benefits of Citizens’ Assemblies, they have increasingly been embedded into the system of democratic decision-making in an ongoing way. This means that rather than being one-off initiatives dependent on political will, they become a normal part of how certain types of decisions are taken, often with a legal or institutional basis underpinning their connection to existing institutions like parliaments.

Embedding citizen deliberation in a systemic way makes it easier and less expensive to organise Assemblies on a range of issues, which can only deepen democratic legitimacy. More Assemblies provide more opportunities for more people to represent others, ultimately giving people more power in shaping decisions. Read more about benefits in section 3.3 of this guide.

When running a Citizens’ Assembly, we recommend treating it as a stepping stone towards a larger shift in democracy. Setting up a Citizens’ Assembly requires effort and leads to in-depth knowledge as well as increased capacity amongst everyone involved. Use the opportunity to build on it to make a systemic shift towards embedded citizen deliberation.

Even if you are starting with one one-off Citizens’ Assembly to address a specific issue, having the intention to make it an ongoing part of decision-making further down the road will help you to capture useful learnings from it. It can help to open up the conversation about how embedded Citizens’ Assemblies could be useful in tackling ongoing policy challenges where citizen input is needed regularly.

Keeping in mind the goal of structural change towards embedded, ongoing Assemblies allows the identification of the necessary legal, social, and institutional infrastructure that might need to be created. This could include, for example, changes to regulations to make Assemblies easier to operate, give them more authority, or pay Assembly Members more easily.

The Assembly should have a clear and simple governance structure that ensures transparency and independence. National level Assemblies with longer mandates have more complex governance with elements such as independent guarantors, a chair and others, while smaller and shorter Assemblies have more simple structures. Typically there are a few groups to bring together.

Commissioner

The commissioner is a public authority, institution, or organisation initiating a Citizens’ Assembly. It ensures that the Assembly has a clear mandate and its results feed into commissioner’s decision-making process. It provides the resources (financial, staff, communications) to run the Assembly.

Operator

The Citizens’ Assembly should be implemented by an arm’s length organisation separate from the commissioning public authority or institution. This helps ensure the integrity of the process. The operator, with expertise in implementing Citizens’ Assemblies, is commissioned to help design the Assembly, recruit Members of the Assembly by lottery, organise the logistics of the Assembly sessions, facilitate deliberation, and prepare the final Assembly report.

An exception here are embedded Citizens’ Assemblies - as the commissioner builds capacity and expertise in running citizen deliberation over time, they are able to run a high quality deliberative process themselves, as part of their function. This takes the form of an independent Secretariat that is charged purely with this function.

There are many non-profit and for-profit organisations specialising in running Citizens’ Assemblies. It is important to choose one that upholds high quality standards, meeting the OECD Good Practice Principles outlined in this guide.

Some of DemocracyNext’s trusted partners are newDemocracy and MosaicLab in Australia, Delibera in Brazil, G1000 in Belgium, MASS LBP in Canada, iDeemos in Colombia, We Do Democracy in Denmark, and Deliberativa in Spain. A longer list of organisations with expertise in Citizens’ Assemblies can be found on the Democracy R&D network website.

Project team

The project team is comprised of the representatives of the commissioner initiating the Citizens’ Assembly and key people from the operator’s team who will implement it.

This group is in charge of the overall process - making sure the Assembly is set for success, has a clear path to impact, and is run on the basis of the OECD Good Practice Principles. They are a bridge between the commissioner and the operator.

Oversight or expert advisory group

An oversight group ensures the independence of the Citizens’ Assembly. For it to be a truly independent source of scrutiny, this role can be undertaken by a university, an independent organisation, or international deliberative democracy experts. The oversight group can help overcome any disagreements between the other groups listed, and acts as an intermediary between the Assembly Members and the commissioner in case of any conflict. This group can also include representatives of different political parties.

Content group

The content group is responsible for putting together the information base that will inform Assembly Members’ deliberations, as well as the wider public. The information base should be accurate, broad, relevant, clear, and accessible. This is fundamental for effective deliberation and crucial for ensuring legitimacy of the entire process.

The content group is comprised of experts in the policy issue of the Assembly representing different perspectives and views. Its members are often academics, independent experts, and other relevant stakeholders. The project team establishes the content group. The composition of this group is transparent.

Evaluating a Citizens’ Assembly helps policy makers, stakeholders, and the general public trust in the process and the recommendations developed by the Assembly. It will also help to establish what went well and what could be improved next time.

An evaluation process should be initiated early on, before design decisions are made. There are multiple possible methods and approaches to assess a Citizens’ Assembly, including surveys, document reviews, interviews, and observation. For longer, national level Assemblies, impact evaluation should be considered as well. For further guidance, see the OECD Evaluation Guidelines for Representative Deliberative Processes.

Who evaluates?

It is essential that evaluations are as independent as possible.

01. Independent evaluations

Independent evaluations are the most comprehensive and reliable way of evaluating a Citizens’ Assembly. They are particularly valuable for Assemblies that last a significant amount of time (e.g. four days or more). These are usually led by academics or specialists who have experience in evaluation methods, expertise in deliberative democracy, and an understanding of what a high-quality public deliberation entails.

A good place to start looking for an evaluator is centres of expertise of deliberative democracy, such as the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin, the School of Geography, Politics & Sociology at Newcastle University, the Department of Political Science at the Pennsylvania State University, and the Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra.

Depending on your context, you may need a local evaluator who speaks the local language. In such cases an option would be to reach out to the political science faculty of your local university. Even though it is quite difficult to find a deliberative democracy expert, local political science researchers could consult or be supervised by internationally established experts to conduct an evaluation. The operator you are working with should also be able to recommend relevant academics in your context.

02. Self-reporting by organisers

Self-reporting by the project team of the Assembly happens as an open discussion among team members in charge of implementing the process, guided by a set of questions. They reflect on lessons learned and what could be improved next time.

03. Self-reporting by Members

Self-reporting by Assembly Members is done by collecting their confidential feedback via surveys and interviews.

What to evaluate?

Evaluation should capture how an Assembly was set up, how it took place, and what impact it had.

Process design integrity

Evaluating the design process that set up the deliberation

- Clear and suitable purpose

- Clear and unbiased framing

- Clear and transparent mandate

- Assembly design aligned with its objectives

- Inclusive process of designing the Assembly

- Transparency and governance

- Representativeness and inclusiveness

Deliberative experience

Evaluating how a Citizens Assembly unfolds

- Neutrality and inclusivity of facilitation

- Accessible, neutral, and transparent use of online tools

- Breadth, diversity, clarity and relevance of the evidence and stakeholders

- Quality of Member judgement

- Perceived knowledge gains by Members

- Accessibility and equality of opportunity to speak

- Respect and mutual comprehension

- Free decision-making and response

- Respect for Members’ privacy

Pathways to impact

Evaluating influential conclusions and/or actions of a Citizens' Assembly

- Influential recommendations

- Response and follow-up

- Member aftercare

How to choose the question and set the mandate?

The framing of the issue influences all other aspects of the Citizens’ Assembly’s design.

The Assembly’s question should:

- Have a clearly defined mandate

- Be related to a genuine problem that needs to be solved. Issues that are complex, involve trade-offs without easy yes/no answers, and are underpinned by values-based dilemmas are often well-suited to Citizens’ Assemblies

- Be framed in a non-leading, unbiased, clear way, that is easily understandable to anybody

- Make it clear how the recommendations will be used and how the Assembly is connected to the broader political system or decision-making cycle

- Be announced publicly by the commissioners and the project team to ensure accountability and transparency

Other considerations:

- Think about what decisions the Assembly can influence to help solve the problem(s)

- Involve stakeholders in defining the question

- Find the balance between a framing that is too broad to result in useful recommendations and too narrow to miss a chance to generate new and helpful ideas

Who will respond to the recommendations?

You need to decide from the outset who will respond to the recommendations, in order to strengthen ownership, clarity, and commitment. It is often the parliament, the municipal council, a government committee, or the executive team of an organisation.

How big and long should the Assembly be?

It depends on the question and the mandate. The more complex, salient, or controversial an issue is, the bigger the Assembly will be and the more time it will need to deal with the issue.

The Assembly needs to capture enough diversity so that everybody feels that “someone like me” is part of it.

Context matters - typically local Assemblies are smaller (around 25-40 people), while national, and transnational Assemblies have been bigger (for example Scotland’s Assemblies have involved 100 people, national Assemblies in Ireland and France have ranged from involving 100-185 people, and the EU-level Assemblies have involved 200 people).

There is an inherent trade-off between efficiency, deliberative quality, and maximising representation. More Members means a longer Assembly and more resources, but also greater representation and stronger legitimacy for recommendations.

The more complex an issue, the more time it needs. The OECD Good Practice Principles recommend a minimum of 4 full days of deliberation (typically 40 hours is a good shorthand). Many smaller or local issues benefit from 6-10 days of deliberation. Many national assemblies have tended to last between 15-25 days. Think about a common sense test: "Would you trust the recommendations of an Assembly on the issue after X amount of time?"

When should the Assembly take place?

- Setting dates and times might seem like a logistical question, but getting it wrong can create barriers to participation and exclude some groups

- Usually Assembly sessions take place during the weekend once or twice per month over several months, especially in national or regional Assemblies where Members travel longer distances to participate

- Local Assemblies can take place on a weekend day, since Members don’t necessarily need to travel far to join

- When choosing the dates for the sessions, keep in mind not to set them during public holidays and celebrations (including those of minority groups), school holidays, and other culturally relevant considerations

Where should the Assembly take place and how to create a deliberative space?

Selecting where a Citizens’ Assembly takes place is a fundamental step in ensuring that the process runs smoothly and that Members feel welcome, comfortable, and empowered.

The spatial conditions of a location can easily enable rich and productive learning, discussion, and deliberation as much as they can hinder it.

Consider first where the deliberative process will take place in relation to the wider region or city, making sure it is accessible by public transport and located somewhere that is reachable by all Members of the Assembly.

In choosing a specific venue, consider choosing somewhere that is large enough and can be easily adapted for organising the Assembly.

Adaptable tables and seating options are essential, as well as wall space for displaying information about the given topic and agreements that have been reached.

The space itself should have lots of natural light and should include the right acoustic conditions to allow everyone to hear and be heard in both larger plenary sessions and smaller breakout groups.

Ideally this means that the space includes both a larger gathering area with smaller adjacent spaces for deliberation and consensus-building.

In traditional government buildings, spaces are organised in a way that doesn’t necessarily accommodate people to sit together in smaller, intimate groups to deliberate on a topic. This may not be the best place for an Assembly.

In what ways should stakeholders be involved in the design process?

Designing a Citizens’ Assembly should be a transparent and inclusive process, led by the project team. It should involve in-house or external deliberative democracy experts.

To ensure the Assembly is widely accepted and trusted by public stakeholders, a process should be set up to involve stakeholders representing diverse views when finalising its design. This could be a meeting or a workshop to share and discuss the plans for the Assembly, or an open call for comments.

To address concerns stakeholders might have about handing over any decision-making power to everyday people, the Assembly process should be explained and ways in which stakeholders can contribute beyond the initial design workshop should be made clear. For example, by including them in developing a list of suggested expert speakers.

How to choose the right digital tools?

There are several ways digital tools can be helpful in running a Citizens’ Assembly:

Facilitating learning — to enable Members to access videos and written materials to learn about the policy issue before the Assembly starts and in between the sessions.

Facilitating connection — to help Members interact, communicate, and build connections and trust in between the sessions and after the Assembly is over.

Supporting facilitation — during the Assembly they can be used to transcribe and summarise group and panel discussions, draw recommendations, and enable voting for the final set of recommendations.

Following up on the results — to help Members stay in the loop about the impact of their work.

Engaging broader society — sharing progress and results of the Assembly, organising other participatory processes that inform the Assembly.

Remember that choosing to use digital tools for Member learning and communication will require support, on-boarding, and providing access to internet and computers or tablets for some Members who may not have access to these facilities.

How to ensure the Assembly is as inclusive as possible?

It is important to ensure equal access to take part in the Assembly for all members of the community.

Find out more:

1. Accessibility

Any person with a disability should be able to reach the Assembly meeting place comfortably and independently, and take part without constraints. Appropriate equipment should be made available during Assembly meetings – such as an induction loop for the hearing impaired, providing a sign language interpreter or additional information on the screen, accompanying voice narration of written text for the visually impaired, among others.

2. Compensation

As highlighted in the Good Practice Principles, people should be paid an honorarium for their time, caring costs and travel and accommodation expenses where relevant should also be covered.

3. Language

Depending on the linguistic diversity of the context in which the Assembly is run, you might need to identify and plan for measures to help Members of the Assembly communicate. These include live interpretation, assigning or allowing Members to bring a paid language buddy who supports them during the process.

What about procurement?

The commissioning authority will most likely need to run a procurement process to select an operator with the knowledge and experience of running a Citizens’ Assembly. DemNext has put together a sample procurement document based on our experiences in Europe. MASS LBP has a guide that may be more relevant for North America.

How to involve the wider public beyond the small group of Assembly Members?

It is worth taking time to consider other activities that can open up participation to a wider public - for example, open calls, interviews, or surveys prior to the assembly, to help understand how communities relate to the issue being tackled. This serves a dual purpose of socialising the work of the Assembly, and providing Assembly Members with valuable insight that forms one part of the wider evidence base for their deliberations.

Another way to keep the broader public in the loop is by gathering questions people might have about the Assembly and the issue it is tackling. Assembly members can answer them in short videos that are later disseminated.

How to ensure the communications strategy helps the wider public and decision makers to stay informed about the Assembly?

A dedicated communications strategy and staff time should be budgeted for and set up from the very start, with the aim of informing broader society about the Citizens’ Assembly, communicating its progress, sharing evidence and learning materials on a dedicated website to inform the public debate, and raising awareness about the issue tackled and Citizens’ Assemblies in general.

Useful ways of spreading the message:

- Organising press briefings

- Live-streaming Assembly sessions

- Inviting journalists to interview Members

- Disseminating press releases

- Running a social media and outdoor poster campaigns

How to ensure high-quality and neutral facilitation?

This is one of the most essential criteria for ensuring the Assembly’s legitimacy and success. Facilitation is a specific skill that requires training, know-how and experience. A clear and detailed plan should be prepared by the operator’s facilitation team that outlines how Assembly Members will go through the process of getting to know one another, learning about the issue they are tackling, deliberating, finding common ground, developing recommendations, and coming to a broad consensus. It should include a mix of work in small groups and plenary sessions.

How does the selection process work?

A defining feature of Citizens’ Assemblies is that Members are selected by lottery to be broadly representative of a community, which means everyone has an equal chance to represent and be represented in turn.

There are two stages to the selection process. In a first stage, a large number of invitations (often between 10-30k) are sent out to a group of people chosen completely at random.

Amongst everybody who responds positively to this invitation, a second lottery takes place.

This time there is a process - known as stratification - to ensure that the final group broadly represents the community in terms of gender, age, geography, and socio-economic differences.

The term for this is sortition. Sometimes it gets referred to as a democratic lottery or a civic lottery.

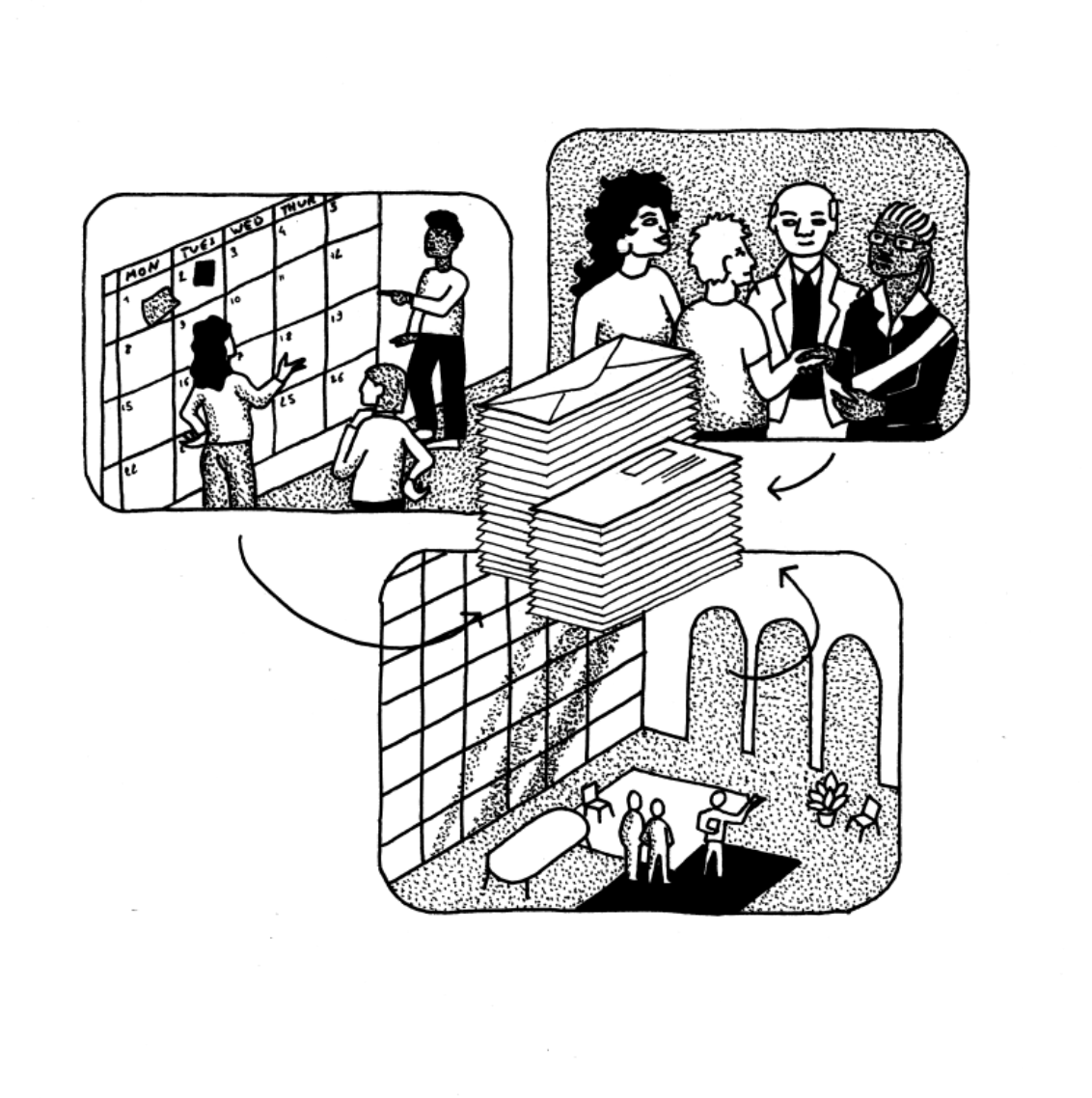

Stage 1

Invitation sent to a random sample of the population (2.000-30.000) by post, phone, email.

Recipients can volunteer to opt in to the lottery.

Stage 2

Second selection by lottery amongst the volunteers. Stratified based on: Gender, Age, Location, Socio- economic criteria etc.

Final Group: Broadly representative of the community concerned (city, state, country etc.)

Who should be responsible for selecting Members?

Members are often selected by the operator and this process is overseen by the project team. The operator should have experience running sortition and should lead this process.

Upon which criteria is the group stratified?

Most often, gender, age, location, and another variable that captures socio-economic diversity (such as level of education or type of employment) are used to put together a broadly representative group. On some occasions additional criteria such as language spoken or people’s attitudes towards the question tackled is collected and used to make sure different views are represented in the final group. Criteria should also be set for excluding elected politicians, in case they receive an invitation. Adding too many criteria should be avoided, as it makes it complicated to put together a group that can capture them all.

Should we oversample the underrepresented?

Traditionally under-represented groups, such as people with lower socio-economic status, young people, those living in rural areas, people disadvantaged by ethnicity, race and in other ways, are less likely to accept the invitation to join the Assembly.

It could be tempting to think that the solution to this problem is to invite people to the Assembly in ways that bypass the sortition process. However, this would create problematic knock-on effects, undermining the principle of everybody having an equal chance of receiving an invitation to be an Assembly Member in the first place. It’s important that everybody in the Assembly feels that they are attending by means of the same process - and as members of a shared community.

If some of the group were to receive targeted invitations, bypassing the lottery process, those Assembly Members could feel that they are present solely to represent a specific group or interest, rather than as a community member who has been selected by lottery. We all have multi-faceted parts to our identities, and Assemblies create an enabling environment for people to be able to reflect on the many parts of who they are and not be reduced to one or two aspects of their identities.

So how to nonetheless overcome the issue that certain demographics often have lower response rates to the initial invitation? There are a few options:

If it is known in which areas people from these groups live, sending invitation letters to more households in those areas to help ensure that their response rate can match those of other groups so that they will be well-represented in the final composition of the group.

Raising awareness about the opportunity to join the Assembly through targeted outreach efforts by community, governmental, and non-governmental organisations.

Working with civil society organisations or community groups that work with underserved communities to distribute more invitations to their members during the first phase of the two-stage lottery process. This means there is some over-sampling that takes place initially, but the second stage of the lottery is still done completely at random, ensuring the final group is broadly representative of the whole community.

At the local level, going door-to-door to people who have received an invitation but have not responded and asking them what could be done to enable them to participate is also a tried and tested technique, though time and resource intensive.

Which data registers should be used?

To send out the first round of invitations, different databases are used depending on availability. These are often the national population registry, voter lists, postal registry, municipal registry, and others. In cases when no database is available, other techniques like random digit dialling or door-to-door recruitment can be carried out. The aim should be to use the most complete list - sometimes a combination of lists - to be as inclusive as possible. Voter registration lists are often poor lists to use on their own for this reason.

Remember to comply with any regulations around the handling of people’s personal information throughout, such as GDPR.

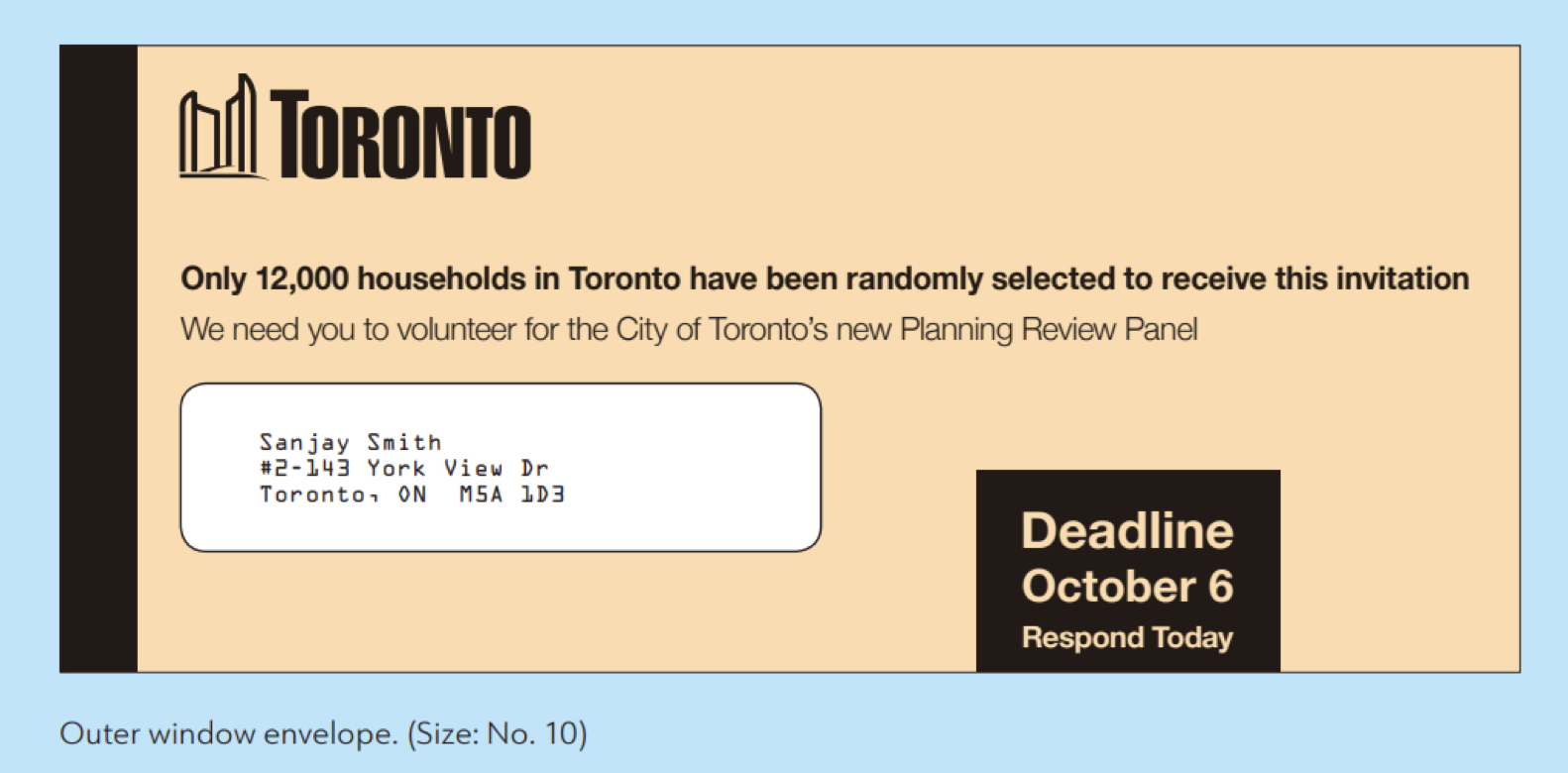

What should the invitation letters look like?

Getting the invitation letter right is very important in order to maximise the response rate of those invited.

Invitations should come from and be signed by the person with the most authority to issue the invitation - this could be the president, minister, city council leader, chief executive, or similar.

The letter should provide all necessary information that would enable the recipient to understand the purpose of the Assembly and whether they are able to commit to the full process.

Invitation letter should include information about:

- The issue and question the Assembly will address

- Who will receive their final recommendations and what will happen after that

- An invitation to put themselves forth for the second lottery to become an Assembly Member

- An explanation about the recruitment process and how to register for the next stage of the lottery

- How the Assembly will unfold

- All the dates on which Assembly Members need to be present

- Remuneration rate (in bold)

- FAQ sheet

The design of the envelope matters - it should strike a balance between looking appealing and inviting, but official enough that people know it is important to open. It is helpful to write the registration deadline on the envelope to catch people’s attention. Context also matters. In some countries, it is helpful for the invitation envelope to look like it comes from the government. In other places, the opposite is true and it should be fun and appealing, rather than official-looking.

What should be included on the FAQ sheet?

A Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) sheet is included with the letter to provide more detail about the process. It gives an opportunity to make potential Assembly Members feel welcome and comfortable. Besides logistical information about the Assembly meetings and clarification of how an Assembly works, it can address practical questions (such as what people are expected to wear, what support is available) and emphasise that there are no special qualifications required to join, everyone is welcome.

How do people reach out with any questions before the Assembly?

It is handy to set up a hotline which potential Members can call to ask any questions, and so that once the Assembly is underway, Members are able to call for help with any issues they might experience. Typically, this is set up by the operator.

How to run the second stage of the sortition process?

Once the list of people who responded positively to the first invitation is available, there are several trusted online platforms with sortition algorithms that can be used to select the final group to be broadly representative of the community. We recommend using one of the following free and open source tools:

- Panelot random selection algorithm

- newDemocracy Stratified Random Selection Tool

- Sortition Foundation StratifySelect algorithm

Assembly Members will bring their lived experience and unique perspectives to the process, but they will need to learn about the policy issue the Assembly will tackle from an accurate, broad, relevant, clear, and accessible information base. This is fundamental for effective deliberation and crucial for ensuring legitimacy of the entire process.

The content group is in charge of preparing the information base: a list of experts and stakeholders that Members will hear from and an information kit.

Find out more:

1. Experts and stakeholders

Prepare a line-up of experts and stakeholders representing a breadth of diverse viewpoints. This is important because it builds trust in the process and ensures no one was excluded.

Map out the different dimensions of the issue - from key areas of disagreement or debate, to expert views and lived experience - in order to ensure that all are covered.

Keep in mind the diversity of the experts and stakeholders in terms of gender, minority groups, and other criteria.

Invite experts and stakeholders to present to Members in person, or to record a video presentation. Each of them should have the same amount of time.

2. Information kit

In the information kit outline the problem, the question, what answers are needed from the Members, the context, the current approach and efforts.

Write it in clear, accessible, written in a simple, jargon-free language.

Include any background reports needed to make the decision.

Aim for 50-200 pages (depending on the complexity of the issue) that explain as much of the problem as possible.

3. Requesting additional experts

Make sure to leave some time for presentations by additional experts, requested by Members during the Assembly, in case they feel that some voices were underrepresented.

It is important for Assembly Members to have some influence over the process and be able to call in their own experts and suggest sources of information.

Different ways people learn

People learn and process information in diverse ways. Recent studies show how different people better learn or retain information depending on how they physically interact with it. Sessions where Members deliberate while walking in nature or visually convey their ideas to others are examples of how this can be done.

Treat the line-up of experts and stakeholders and the information kit as the starting point of preparing learning materials and evidence for Members. Also consider including other elements, such as field trips, games, and other ways of interactive learning.

Remember that other kinds of knowledge beyond scientific or experiential - such as embodied knowledge or indigenous knowledge - are welcome, sought out, and valued.